LSTM Neural Networks and Music

If you have ever watched the movie The Blues Brothers, you have seen one of the most influential bassists of all time, Donald “Duck” Dunn. The list of songs and recordings Dunn has played on is so long, wikipedia has broken it out into its own entry. Dunn has long been an influence on my playing and someone that I have always enjoyed listening too. This post is dedicated to his incredible contributions to music and bass playing.

Time Series Forcasting

One common problem that data scientists face is trying to predict data based on a previous sequence of data points. Recurrent Neural Networks or RNNs are a useful tool to use on these types of problems. Jason Brownlee, PhD. has two nice blog posts on this subject.

As I have done in previous posts, I was curious if I could use this technique and apply it to something of interest to me.

A Different Angle

One of the things that I enjoy doing outside of researching data science, being a family guy, and practicing Taekwondo, is playing music. I am a semi-professional jazz bassist. That means that I am basically a music snob, and play jazz music for tens of dollars once a month or so.

I am faced with a kind of time-series problem when I play the blues. That got me wondering if I could train a Neural Network to do it. If I can do it and Homer can do it, surely a neural net can too!

Playing the Blues

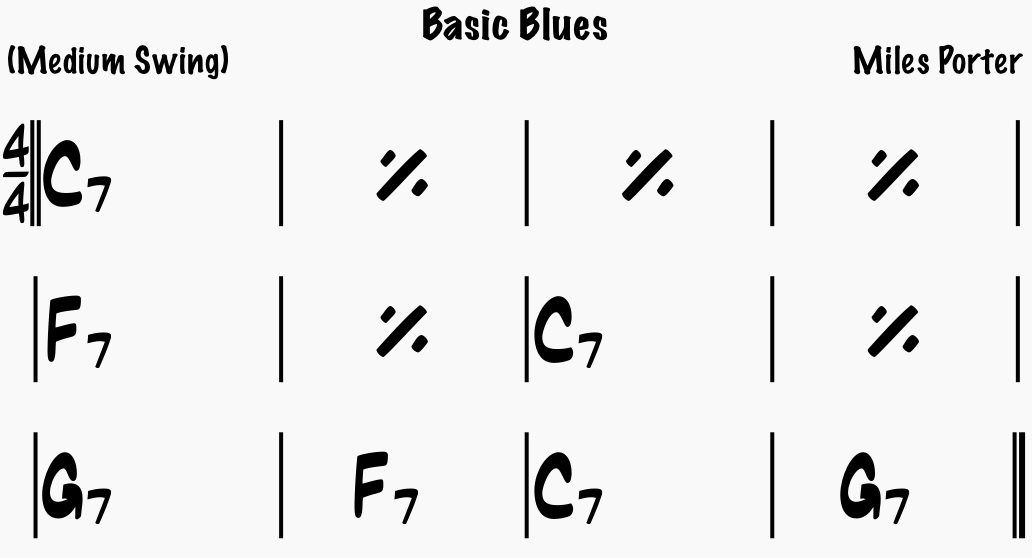

Without going too deep into music theory, a 12 bar blues has a chord progression that looks like this:

As a jazz bassist, my job is to look at the chord changes above and make up a bass line that fits those chords. When the song is played “swing style” the bars all have 4 beats. In that case, a jazz bassist will usually play one note per beat. This is called playing a “walking bass line”.

If I see a C7 chord, I know that it has the following notes:

C, E, G, B flat

If I see the F7 chord, I know it has the following notes:

F, A, C, E flat

As a bassist, I could just pluck out the notes above, but it wouldn’t sound very good. Jazz “cats” would say it sounds “square”. In jazz, there are no wrong notes, but some notes are more “right” than others.

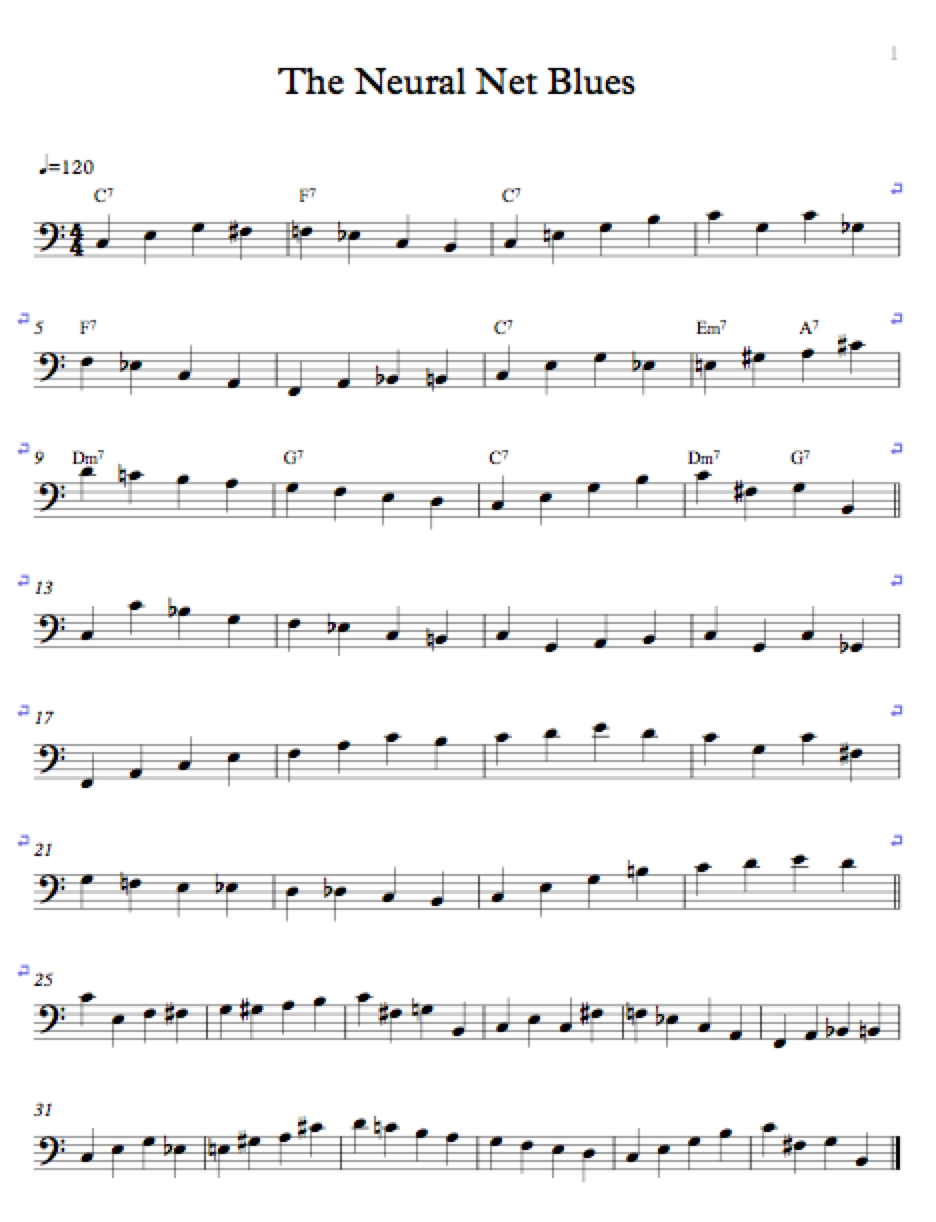

The challenging and artistic aspect to playing walking bass lines is to come up with a line that makes sense with the changes, but also flows smoothly. This means that while I will emphasize the notes in the chord in my bass line, I will also use other passing notes that fit the key, and make things flow. Here is an example bass line that I created over a slightly modified blues that I call “The Neural Net Blues”.

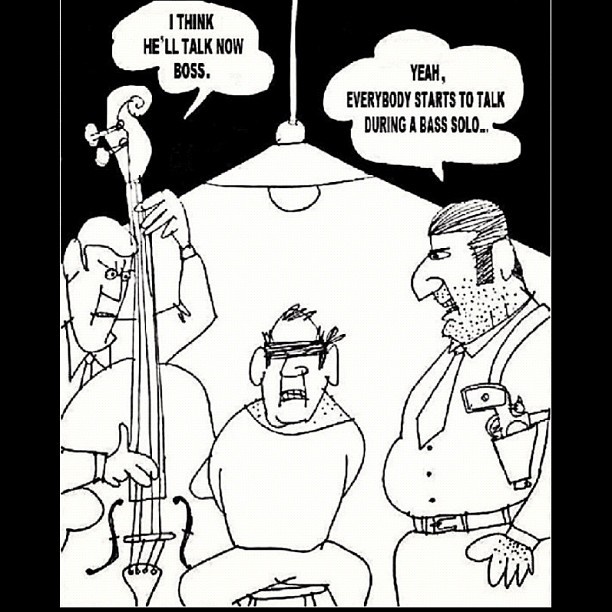

You may have noticed that the song is longer than 12 bars. That is because a blues is played by repeating the blues chord changes. The Neural Net Blues has 36 bars, or three choruses of the changes. The idea here is going to be to create a neural network to learn the blues based on the first two choruses, or up through bar 24. The last 12 bars of the song will be reserved for the neural network to play over. You can think of them as a sort of a computerized bass solo. That is doubly doomed to have virtually nobody ever listen to it; first because it is computer generated, and secondly because it is a bass solo.

Preparing the Data

In order to train a recurrent neural network to learn the blues, we need to do a couple of things. First, we need to convert the notes to values. Next, we need to scale those values into something that the network can learn. The learning system basically works like this. We take the first note in the training line, and then train the network to predict the second note. Next, we take the first two notes in the training set and train the network to predict the third note. We continue this process over the entire training set. We will also perform this operation in multiple batches.

The note values that we will use will be MIDI note values. MIDI or Musical Instrument Digital Interface is a specification that allows us to generate music on a computer. You can read more about it here. One nice thing about MIDI and Python is that the pygame module that I have used in the past (see the blog post Saving Humpty Dumpty) has a nice wrapper for working with MIDI.

We will use the same approach for scaling the values of the MIDI file as used by Dr. Brownlee in his blog posts mentioned above.

The Network

We will use the same structure for our neural network as the one used by Brownlee.

model = Sequential()

model.add(LSTM(neurons, batch_input_shape=(batch_size, X.shape[1], X.shape[2]), stateful=True))

model.add(Dense(1))

model.compile(loss='mean_squared_error', optimizer='adam')

Results

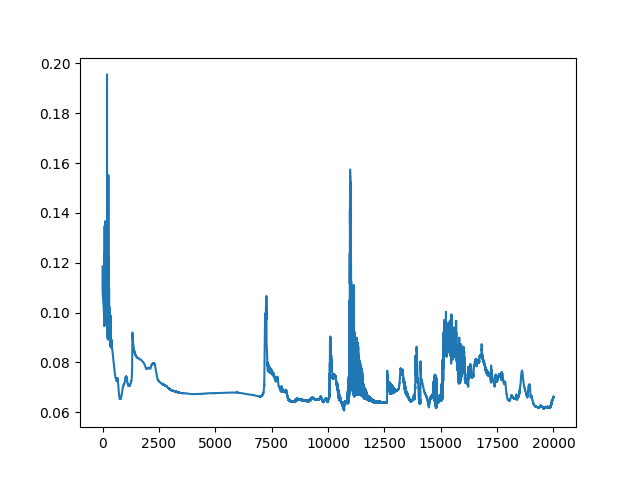

I trained the above network over the data using the same approach as Dr. Brownlee over 20k epochs and got a learning curve that looks like this:

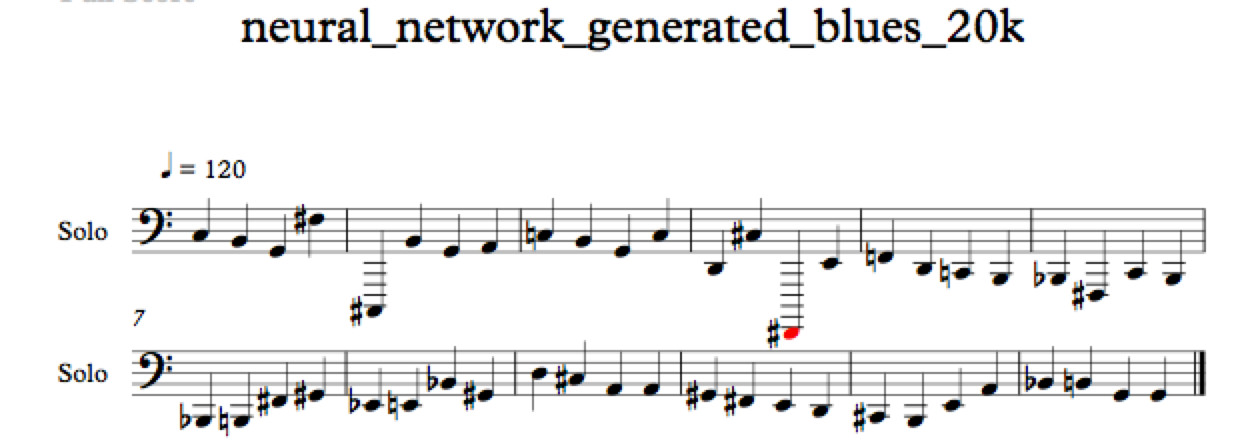

Here is the bass line that the network came up with (with an 8 beat lead-in).

Hmm. I’ve heard (and played) worse, actually.

Anyway, there are some obvious issues with this bass line. First off, a good portion of it is outside of the range of the bass. There are also some pretty bad “clams” in there, as Pat Metheny would say.

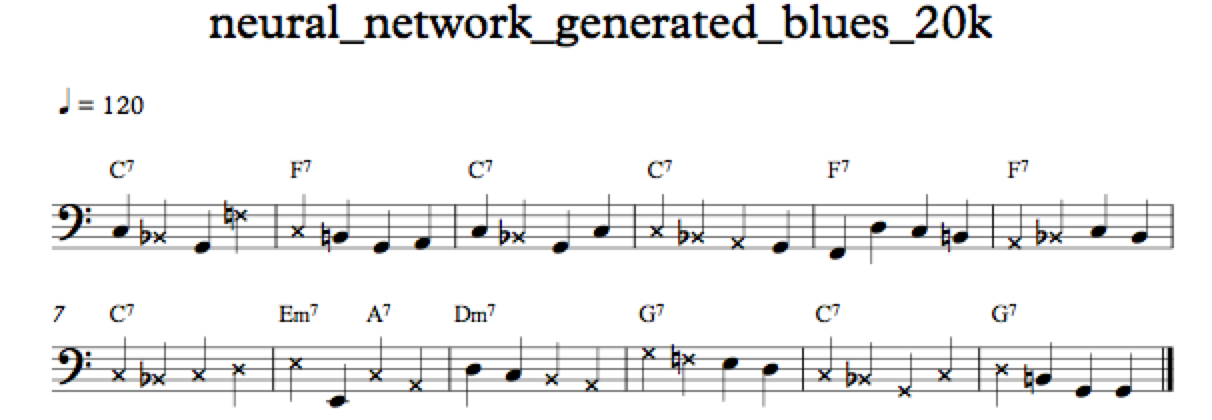

Maybe we can help this situation out a bit. In the above, I have modified the line by moving notes up an octave when they drop below the range of a standard bass. I have also shifted some of the notes (the ones with Xs) up or down in order to make the line a little nicer. This is still largely the line that the net came up with.

Well… I don’t think were gonna get a $10k advance on our first recording session with Clarion Records (skip to 1:26), but it sorta sounds like music. Maybe?

Where from here?

The time series problem that I have tried to solve here is basically building the baseline with the only input being the training set. That is sort of antithetical to the idea of playing jazz. Jazz musicians are supposed to listen to each other, and not just themselves. My high school band teacher Mr. Zachman had a term for people that didn’t listen to others when playing. He would say that they had perfect ears.

Perfect ears have NO HOLES.

One different approach we could take with this exercise would be to still use a recurrent neural net, but rather than having the input be the previous notes in the bass line, have the inputs be the chord tones from the previous or even the current beat. A bassist looks ahead when playing. They know what chord is coming, they don’t just look back, which is what this model is doing.

At any rate, the goal here was to explore. While working on this, I came up with a different and more realistic data set to use for recurrent neural networks.

My next blog post will be on this other data set, and reading it will be like watching paint dry. I guess you’ll just have to read it to see what I mean!